THIS POST IS THE FIFTH IN A SERIES OF DAILY CONFERENCE RE-CAPS WRITTEN BY EARLY CAREER SCHOLARS ATTENDING THIS YEAR'S CONFERENCE.

❦

By Loren Cressler

I know that Meghan Andrews wrote yesterday about the critical conversations around authorial collaboration, and I am nevertheless compelled to write a post today thinking through the values of our ongoing scholarly relationships. Whether or not we are directly collaborating and co-authoring, we are constantly advancing one another’s work, and the relatively intimate nature of the MSA conference means that we do so in real time, collectively. Listening to panels in which the presenters have cultivated an ongoing conversation over months or years gives one the impression that our relationships yield increasing returns as we maintain them.

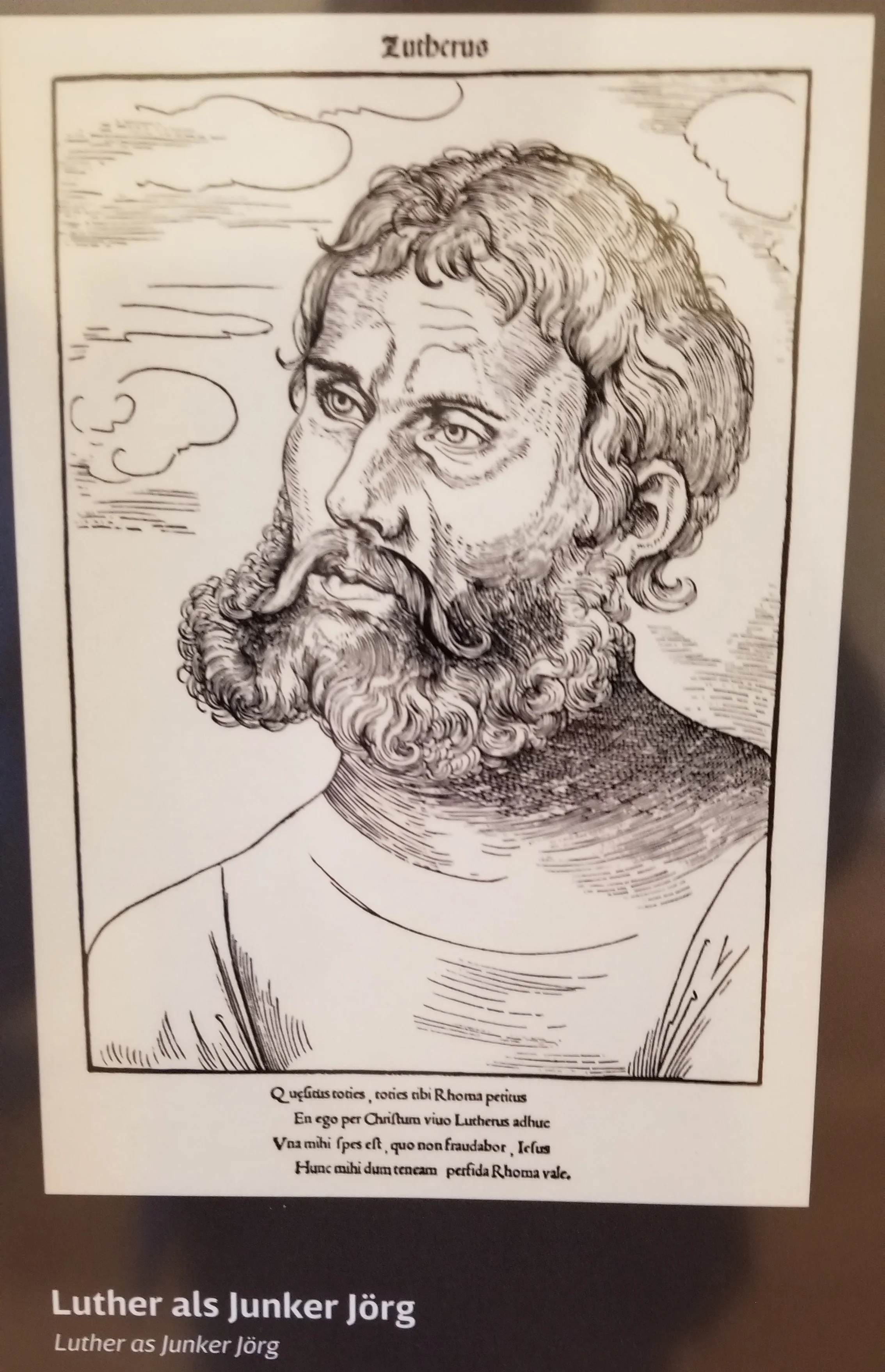

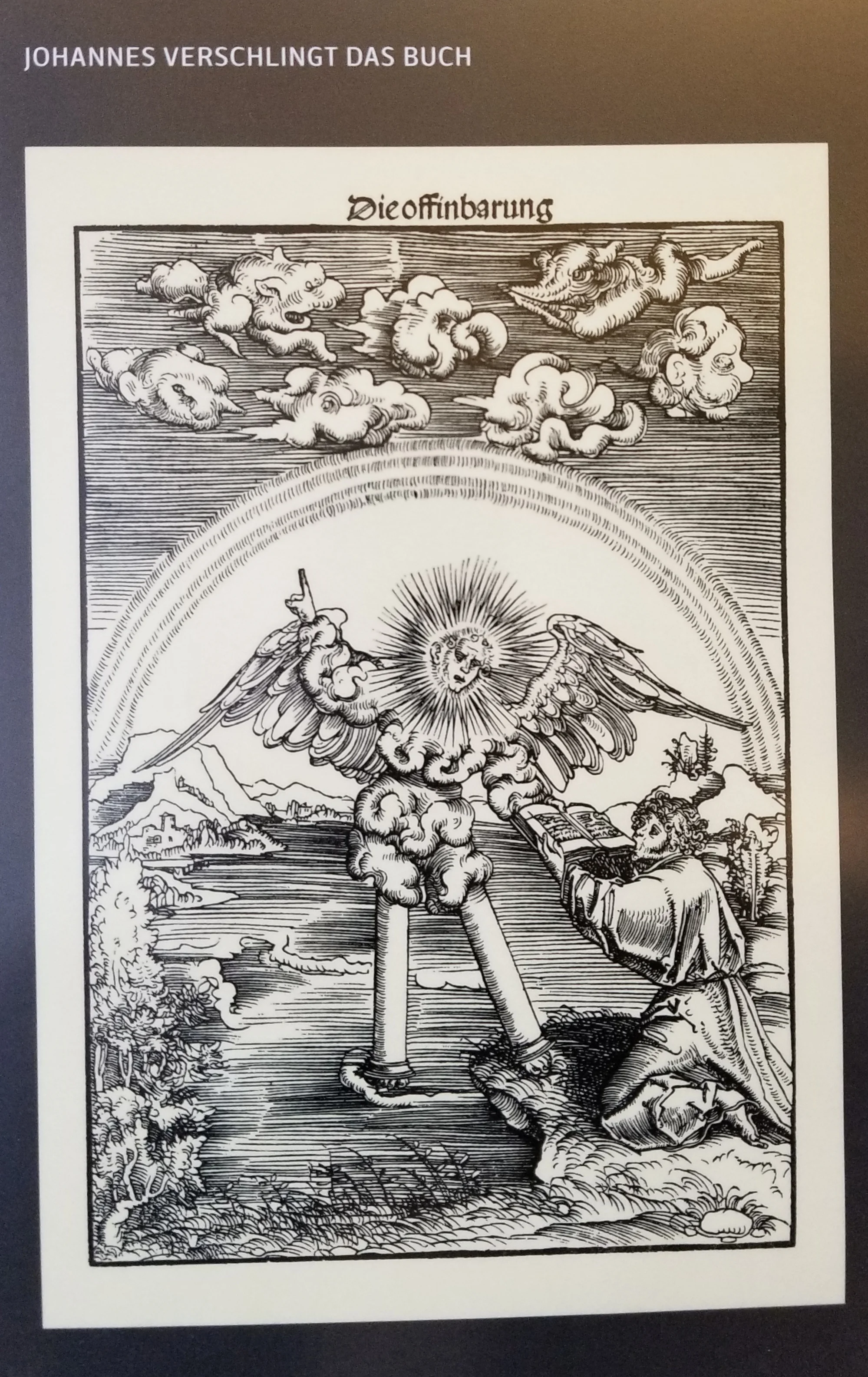

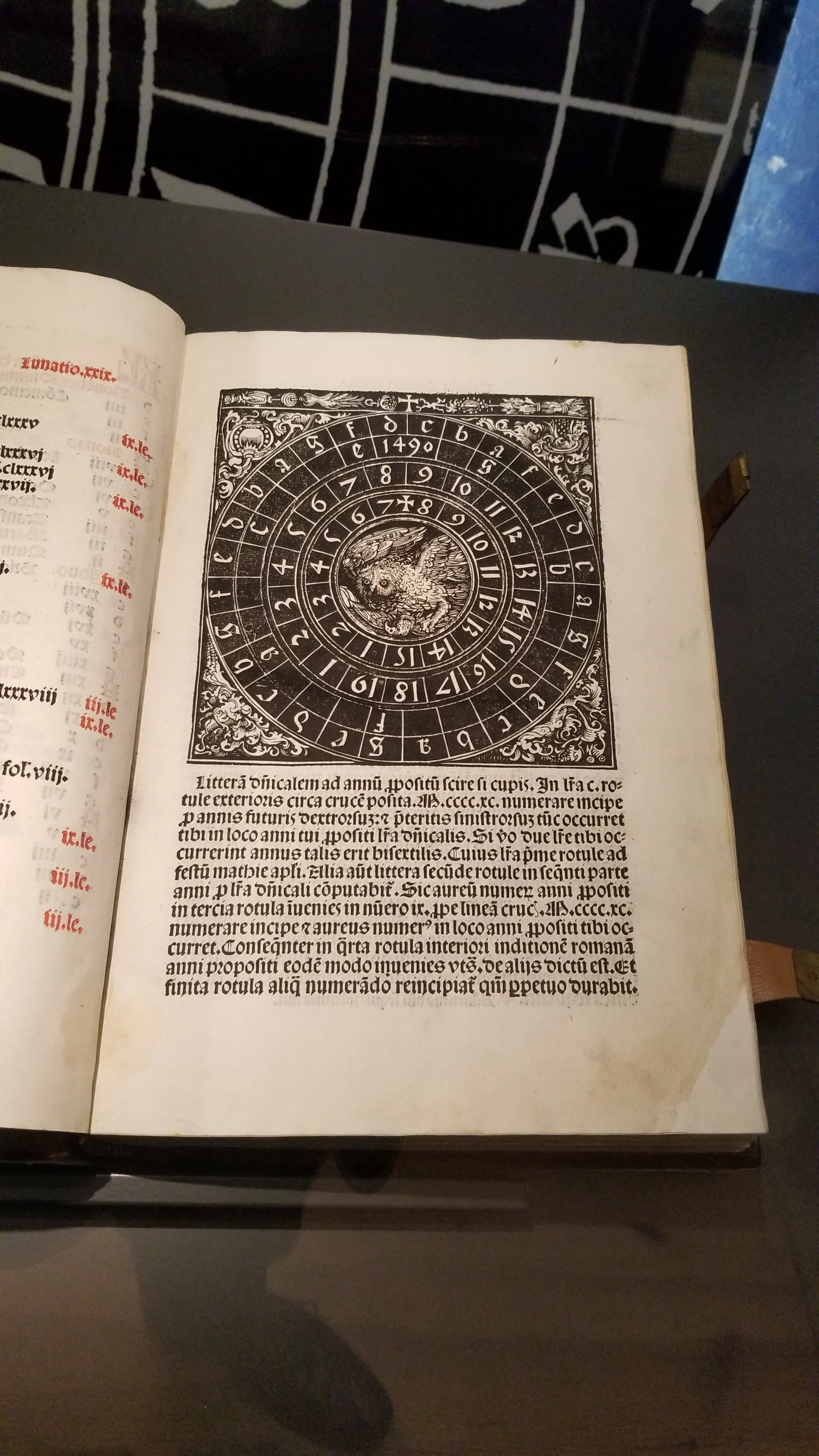

I will return to the MSA proper shortly, but first, a brief shadow or typology. In Wittenberg, we are incredibly fortunate to see the fruits of what was surely one of the richest and most consequential partnerships of the past half-millennium. Philip Melancthon, Lucas Cranach the Elder and Martin Luther maintained lifelong friendships as Melancthon and Luther held the public disputations and wrote the theological treatises that began the Reformation. Luther’s first translation of the New Testament, called the “Septembertestament” and published in 1522, featured woodcut illustrations throughout by Cranach, and Cranach produced numerous portraits of Luther throughout his lifetime. Because of their relationship, we know what Luther looked like from the time he arrived in Wittenberg as a young monk and can witness his incarnations as a recently hooded doctor, a fugitive with the alias “Junker Jörg,” and as the robed theologian many of us recognize. As with our own scholarly relationships, Cranach and Luther’s friendship yielded increasing returns and generated invaluable written and pictorial documents of both men’s working lives.

In our little corner of Wittenberg between the Lutherhaus Museum and the Cranach workshops, we are also reaping the fruits of years or decades of acquaintance, friendship, and intellectual engagement. In Thursday’s first session of panels, Adam Hooks, Vin Nardizzi, and Megan Heffernan presented a series of papers about “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.” Their ongoing discussions before the conference about Marlowe’s poem were evident in the papers, all of which cast new light on this “limpid but slight” lyric.

The conference’s second keynote speaker, Kristen Poole, followed the morning session with a fantastic exposition of 16th-century exegetical culture. By rethinking the concept of the Bible and the existence of a culture of Biblical hermeneutics, Poole located the project of teaching close reading in both 16th-century public sermons and in Marlowe’s dramatic corpus. In early modern sermons and biblical culture, listeners and readers learned to recognize shadows of themselves in historical and mythic circumstances and to read the present in and through the past and future. Marlowe asks both his characters and audiences to think in terms of shadows (which later came to be called typology) when he has Tamburlaine simulate the riders of the apocalypse through the progression of colors he presents to besieged subjects. Finally, Poole wondered, where are the studies of Marlowe and his Bible, given the rich ongoing conversation around Shakespeare and his Bible?

Poole’s keynote concluded the morning session, and as we walked around the city for lunch and Freizeit, my sense of a Marlovian community was strengthened by the unavoidable encounters with conference-goers in all corners of Wittenberg. Luther, Cranach, and Melancthon’s Wittenberg, much smaller than the present city, must also have facilitated many such chance opportunities for a quick exchange of ideas while on the way to something or somewhere else.

In the afternoon sessions, several speakers presented modes of conceptualizing relationships and networks beyond the interpersonal. Andrew Bozio discussed the inseparability of bodily and literary form through the example of Edward Alleyn’s Tamburlaine, whose particular gait signified both a type of acting and a form of drama for decades. Megan Snell spoke about the collaborative relationship between puppeteer and puppet, each of whom depends upon the other. The puppet is of course subordinate, powerless without the puppeteer, but it also retains the ability to distract, interrupt, and sometimes literally punch up at its handler. By expanding their focus beyond interpersonal collaboration to the mutually constitutive relationships between actors’ bodies and their roles, Snell and Bozio suggested avenues for considering human collaboration with both one’s own body and with the non-human.

To round out the day, I met up with my own colleagues, friends, and co-conspirators who are here with me from Texas. We’ve rented some bikes in town and have been exploring the Elberadweg, a bike trail that cuts diagonally across Germany and through Wittenberg. It begins in the Czech Republic at the source of the Elbe and runs all the way to the North Sea, connecting the cities and villages along the way for cyclists. Viewing the Schlosskirche and the Stadtkirche from 5-6 kilometers outside of town was a perfect way to process the day’s discoveries.

One final note on my preferred interpretive shadow for this week: Luther wrote in 1523, “I wish with all my heart to publish nothing at all anymore, because I am tired of writing such things. But Lucas’s press requires upkeep…” May the burdens of publication we undertake be primarily in the service of our communities and relationships, and may they be as fruitful as Luther and Cranach’s.

[All images from Cranach Haus Wittenberg in the slideshow above have been used with permission of the Cranach-Stiftung Wittenberg. www.cranach-stiftung.de]

Loren Cressler is a PhD candidate in the English Department at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is finishing a dissertation called “Malcontented Thought and Dramatic Form in Early Modern England.”