To my fellow Marlovians, I want to take a moment to thank you for trusting me to serve as the President of the Marlowe Society of America for a four-year term. While my first involvement with the MSA was only recently, in the wonderful conference in Deptford in July 2024, the camaraderie and collegiality of the delegation struck a chord with me, and I know from conversations with other members that they hold the Society dear to their hearts. For that reason, when asked to accept a nomination for the Presidency, I agreed with a full sense of my responsibility to maintain the qualities that make this a special Society for its members and even to strive to enhance these qualities. I wish to thank everybody who has already conveyed good wishes to me on the announcement of the election result. Now, if I may, to misquote Mephistopheles, allow me to be bold with your good cheer. The MSA is a truly international organisation, which poses a number of challenges to the executive group to ensure we provide value for the membership. The global reach of the Society was especially tested during the years of the pandemic and there were natural delays in various activities. The incoming executive group (elected officers and appointed roles) have already benefited by inheriting solutions the previous executive put in place to get the Society on track. Even as we face new global crises, the incoming executive is already working to build on their momentum. Watch this space as we aim to give you more reasons to consider the MSA your favourite scholarly Society in the world.

MSA at MLA 2025: Marlowe and Writing

The Marlowe Society of America is thrilled to sponsor a panel on “Marlowe and Writing” at the 2025 MLA Convention in New Orleans. Our speakers’ papers will consider questions around aesthetics, rhetorical style, and philology, and their impact on our understanding of social hierarchy, sexuality, theatre history, and subjectivity.

Please join us on Saturday 11 January from 5:15 to 6:30 p.m. at the Hilton New Orleans Riverside (Marlborough B, 2nd Floor) if you are attending MLA! More information about the venue can be found in the MLA program. Titles and abstracts appear below.

Stateliness: On Christopher Marlowe and Aesthetic Elitism

Adhaar Noor Desai (Bard College)

Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine plays reveal “stateliness” to be a problem shared across early modern rhetorical, political, and aesthetic theory. After explaining how stateliness became an aesthetic shibboleth for Elizabethan elite culture unifying rhetorical style, behavioral protocols, social pedigree, and educational attainment, my paper reads Tamburlaine as dramatizing both its powerful allure and its insubstantial hollowness. Studying Marlowe’s depiction of stateliness alongside contradictions within rhetorical theory’s conception of the “grand style,” the evolving conception of the early modern state between Machiavelli and Hobbes, and sociological accounts of the emergence of elite aesthetics, I argue that Marlowe neither wholly subverts nor endorses the elitism implicit in stateliness. Instead, his work decouples stateliness from existing social hierarchies by treating literary craft as synecdoche for statecraft, or poetic license as continuous with both the responsibility and the self-assured decisiveness required of princes.

Queering Dido: Virgilian Echoes in Marlowe’s Edward II

Bailey Sincox (Princeton University)

This paper focuses on Edward’s pejorative question to Mortimer et al. in Act 5 of Edward II: “Inhumaine creatures, nurst with Tigers milke, / Why gape you for your soueraigne’s ouerthrow?” Observing that this conceit distills Edward II’s de casibus plot and its gender politics, the essay approaches the tiger nurse via “queer philology.” Because this figure also appears in Marlowe and Nashe’s Dido, Queen of Carthage––in lines surprisingly faithful to Virgil’s Aeneid 4––the paper demonstrates that Edward inhabits Dido’s position of feminine complaint. Furthermore, it argues that this Virgilian echo’s figuration of nonnormative reproduction is suggestive for considerations of authorship and “influence.” Turning to a related tiger trope in The True Tragedie of Richard, Duke of York, the paper brackets Marlovian attribution to consider echoes of Marlowe’s Virgil as a repertory phenomenon, the product of (to quote Jeffrey Masten out of context) “a queerer and more plural generation, labor, and dissemination.” Supporting this account are linguistic affinities in a third Pembroke’s play, Titus Andronicus, totaling three of the company’s four or five known plays. This new reading of Edward II suggests that queering Dido played a vital role not only in Marlowe’s writing, but also in the development of the history play and the remediation of classical epic on the English stage.

Marlowe and Writing ‘Methinks’

Heather Hirschfeld (University of Tennessee, Knoxville)

I address in this paper Marlowe’s use of an obsolete term, the impersonal verb ‘methinks’. Drawing on recent philological approaches to the period’s literature, I consider the ways in which the term’s grammatical structure embeds complex approaches to the subject and object of mental experience. I look first at how ‘methinks’ condenses––‘in a little room’, as it were––negotiations of intention, perception, and attitude. I then turn to Marlowe’s use of the term in key moments of Tamburlaine, The Jew of Malta, and Edward II, where it organizes the plays’ broader concerns with political judgment and religious identity. I conclude by considering the way this form invites us to consider the “impersonality” of Marlowe’s characters as they cast themselves as subjects and objects of thinking.

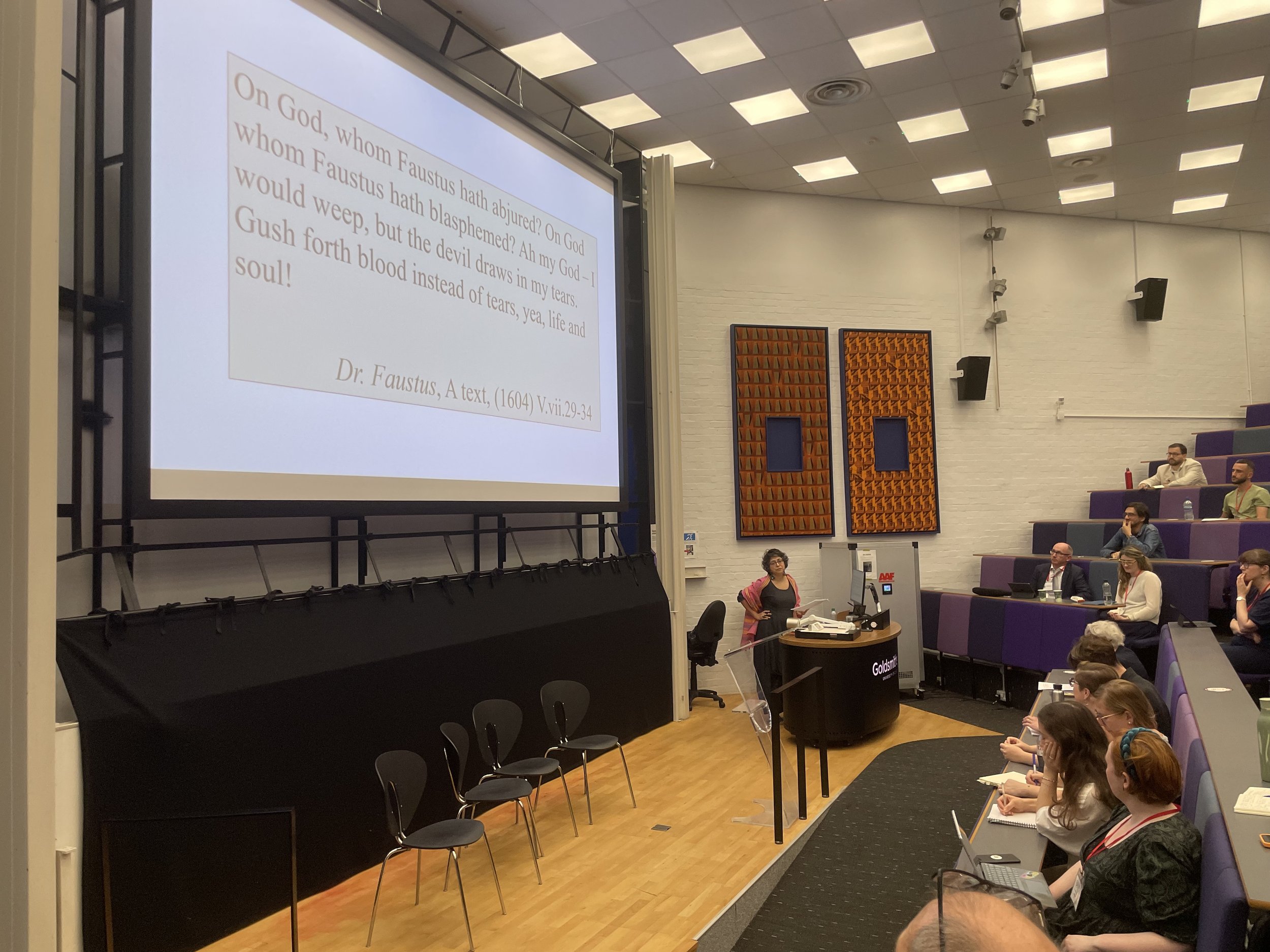

Memory & Commemorations • Day 4, MSA Deptford 2024

We closed out the conference with a very full Friday. The day began with the Meghan C. Andrews Memorial Lecture in honor of our brilliant friend and colleague who passed away last year, far too young. Eoin Price of the University of Edinburgh spoke about performance, time, and repetition in his talk “Doctors Faustus: Repeat Performance and Audience Response.” After a number of panels, we finally adjourned to the Master Shipwright’s House on the bank of the Thames for our closing banquet. The food was delicious, the views were fantastic, and the company was, as ever, exemplary.

If you want to stay up to date with the MSA (including information about our next conference), please consider joining the society. You can find information about membership and how to join on our MEMBERSHIP page.

Research on Foot & in Action • Day 3, MSA Deptford 2024

The third day of our Ninth International Conference in the environs of Deptford featured a series of morning panels. Delegates then traveled west to Bankside and the City for a walking tour of “Marlovian(ish)” places of interest—the Rose, King’s Wardrobe, entry to Blackfriars, Blackfriars, and Donne’s house (the Deanery)—led by the inimitable Tracey Hill. Many delegates also enjoyed special access to the Rose Playhouse site. The day finished with a terrific Research in Action workshop at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse (Shakespeare’s Globe), led by MSA President Lucy Munro and Sarah Dustagheer of the University of Kent. The workshop focused on Marlowe’s plays in repertory and set scenes from Tamburlaine and Dido alongside scenes from Selimus and Wars of Cyrus. Many thanks to actors Suzanne Ahmet, James Barnes, Anna Crichlow, and Kwami Odoom for workshopping the scenes with us.

For more MSA news, follow us on our social media channels at Bluesky (@marlowemightyln.bsky.social), X/Twitter (@MarloweMightyLn), or Facebook. You can also explore the full conference program here.

"Little Echoes of Things" • Day 2, MSA Deptford 2024

BY GUEST AUTHOR PATRICK DURDEL, UNIVERSITY OF LAUSANNE

Let me play the New Historicist for a moment and start with an anecdote.

As I was hurrying (a bit delayed by life) to the first morning panel on "Biblical & Classical Marlowe", I saw some people preparing something on Goldsmith's College Green, right outside the building where our panels are held. In my mind, tired and rushed, I framed this as activity that must be vaguely related or in some way similar to the students setting up their art exhibition in the same building the day before: something will be happening here. So, imagine my surprise when, on my way to the coffee break, there was no film or photoshoot on the Green, no performance or dance rehearsal, but instead what seemed in the moment like a thousand primary school aged children: sack-racing, spear-throwing, tug-of-warring. Certainly, I thought, this must mean something.

In fact, I realized during the coffee break, I should have been prepared for this. In her paper and during the Q&A, Ruth Lunney had repeatedly mentioned the children performing (& potentially watching) Dido. And luckily, all three papers in the "Early Modern Acting" panel helped me make further sense of what was happening outside: the skill involved in falling, for example, the intricate language of fencing (with foam spears), and how all this was a way for the children (or child actors) to learn the necessary skills for a successful career on the stage. Nice.

Then I had some lunch, went to the "Marlowe and Materiality I" panel, and realized that I had gotten it completely wrong. I had misunderstood the evidence available to me. In fact, this question of what we know, the challenge of how little we often know, and how we can (methodologically, theoretically, practically) deal with this uncertainty figured in some way in almost every paper I heard yesterday. Laurie Johnson used the scarce evidence to paint a vibrant picture of Tamburlaine on tour, and Anouska Lester explicitly prompted us to explore and interrogate the constellations of the different kinds of evidence we use in our scholarship. This connected seamlessly, I felt, to the discussion of editorial practices in the afternoon's plenary panel on "Re-Editing Marlowe for the Modern Reader". And Subha Mukherji's keynote further added to the "Notes on Evidence" hastily typed into my phone, by underscoring, in one of the for me most memorable moments of the paper, the inherently theatrical quality of false legal evidence (false tears, in this case).

There is more to be said here and there are more questions to be asked. But I am sitting on the rush hour-filled tube on the way to Deptford and writing this in my notes app and I should eat something, and I have my own paper to worry about. (I also want to apologize to everyone I did not mention here by name, it is not because I did not appreciate your paper but because I had to commit to my little anecdote from the beginning.)

In the morning, Ruth Lunney told us: "There is no evidence, we are looking for little echoes of things". Violently taken out of context here, the statement might seem a bit too general at first, but so many of the panelists yesterday displayed a great talent for listening closely to faint echoes, making sense of what they heard, and telling us about it. And it was thrilling to listen.